Political prisoner - a definition

In colloquial settings and for ease of use it is useful to use the definition of a political prisoner as any individual imprisoned on politically motivated grounds. The Council of Europe offers an exhaustive and technical definition, that, while no Central Asian republic is a member of the council, applies to thousands of individuals across Central Asia: “A person deprived of his or her personal liberty is to be regarded as a ‘political prisoner’:

- a. if the detention has been imposed in violation of one of the fundamental guarantees set out in the European Convention on Human Rights and its Protocols (ECHR), in particular freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of expression and information, freedom of assembly and association;

- b. if the detention has been imposed for purely political reasons without connection to any offence;

- c. if, for political motives, the length of the detention or its conditions are clearly out of proportion to the offence the person has been found guilty of or is suspected of;

- d. if, for political motives, he or she is detained in a discriminatory manner as compared to other persons; or,

- e. if the detention is the result of proceedings which were clearly unfair and this appears to be connected with political motives of the authorities.”

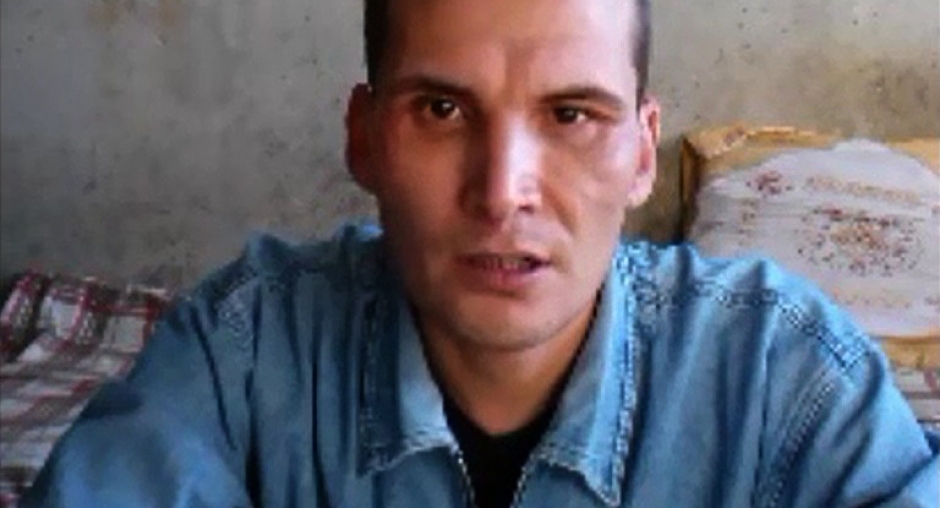

In 2015, on September 28 renowned Tajik human rights lawyer Buzurgmehr Yorov talked to local press in Tajikistan’s capital Dushanbe. Yorov had recently taken on the defense of several recently arrested members of the peaceful political opposition, a dangerous move in today’s Tajikistan and one that would cost him his freedom and health. In the interview Yorov told the press that authorities had tortured one of his clients in pre-trial detention and that officials had planted weapons and explosives in the homes of some. And then when the regime learned that he had told the journalists of his intention to form a committee of lawyers to defend the numerous detained opposition members, wheels were quickly set in motion. The authorities reacted swiftly, and police took the fearless lawyer away already on the same day – apparently without the delay normally caused by rational thought processes.

As happens so frequently in Tajikistan and the other Central Asian republics, authorities soon enough conjured up a wide array of bogus charges against him. And predictably, next year a court found him guilty of fraud, forgery, extremism as well as so called public calls to conduct extremism, along with incitement to national, ethnic, racial or religious hatred. He was sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment. However, dooming an innocent man to 25 years under horrid prison conditions, did not quench the bloodthirst of the regime. After all, Yorov had not only willingly posed an obstacle to their plans to swiftly – and in violation of all human rights conventions – dispose of the political opposition; he had also revealed to the world the Tajik regime’s routinely torture of political opponents. And so, Yorov’s family and relatives soon found themselves at the end of a ghastly government campaign of intimidation, harassment and persecution, culminating not when authorities detained his brother, but with threats of state-sponsored child rape as officials threatened to rape his underage niece. And as though in a bid to prove beyond doubt the absurd and systemic injustice of the Tajik justice system, and court took it upon itself to sentence him to a further three years in 2017 – for insulting the “Leader of the Nation”, Tajik president Emomali Rahmon. Later the same year prison guards would brutally bludgeon him to the point where he now endures difficulties walking normally.

Being exceptionally brutal by most people’s standards, Buzurmehr Yorov’s case tragically is no exception by the Tajik regime’s standards. Rather it serves as a sobering symbol of how the authorities in recent years routinely abuse its own people and torture and imprison anyone who dares getting in their way. In the last handful of years, the regime has viciously tightened its grip on society, unleashing a full-blown human rights crisis and destroying fundamental freedoms along with the political opposition. Disturbingly, in addition to Yorov, at least five other lawyers have been detained or arrested during the current crisis, several of which still remain behind bars, while hundreds of opposition members have been imprisoned. And, if seen in a wider context including all five Central Asian republics – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan – Buzurgmehr Yorov becomes just one out of thousands of political prisoners.

The Central Asian picture

Central Asia is a diverse region differing in culture, tradition, history and language. All the same, last century left the five republics with a shared Soviet legacy that still shapes life in the region through high levels of corruption, low respect for human rights, restricted political freedoms. In all five Central Asian republics political prisoners languish behind bars, although the extent varies greatly between Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Most striking at the moment perhaps is the contrast between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

Signs of progress in Uzbekistan

While Tajikistan is in the midst of a brutal crackdown on rights, Uzbekistan currently appears to be going through what resembles something of a thaw. The death of Uzbek dictator Islam Karimov in the second half of 2016 triggered discussions about the country’s future. While the overly optimistic numbered few, fewer even were those who imagined matters could possibly grow any worse.

During his reign since independence from the Soviet Union, Islam Karimov had effectively formed Uzbekistan into a brutal and totalitarian police state. The security services controlled all aspects of Uzbek life and ravaged the country with impunity. Prisons became storage units for dissidents, critics, journalists, religious practitioners, human rights defenders, activists and others viewed unfavorably by the regime, while torture came to be endemic. There existed no political freedoms to talk about while talking about political freedoms would ensure anyone a lengthy prison service, often after several rounds of cruel and callous torture.

Things went from very, very bad to much, much worse in 2015 when government forces in the city of Andijan surrounded and indiscriminately fired into crowds of demonstrators, killings hundreds of peaceful men, women and children. Following the massacre, the regime pursued isolationist policies and expelled from the country international human rights groups and media agencies. Authorities then unleashed a severe crackdown on civil society and significantly tightened the screws on society in general, turning the country into one of the world’s most oppressive regimes. When Islam Karimov perished on September 2, 2016 his regime had imprisoned thousands on politically motivated grounds.

After ascending to the presidency in the wake of Karimov’s death, former prime minister Shavkhat Mirziyoyev has implemented certain steps to reverse the former regime’s isolationist policies and improve the country’s abysmal human rights situation, and dozens of political prisoners have been released. Mirziyoyev’s Uzbekistan has allowed back into the country some international human rights groups and news agencies, and initiated some reforms – a law outlawing the use in court of evidence obtained under torture has been signed, signaling a will to do at least something with the systemic torture characterizing Uzbekistan’s pre-trial and prison facilities. Mirziyoyev has moreover fired the head of the security services and set in motion certain steps to diminish the its power and control over the country. The new leadership has also expressed intentions to combat the widespread use of forced labour in the cotton sector, although recent reports relay that the problem remains a common occurrence.

The future only will reveal to what extent Mirziyoyev’s presidency will bring about systemic improvements of Uzbekistan’s human rights record, and to what degree his actions and words are mere window dressing designed to please an international audience. For now, however, cautious optimism gains traction as the regime releases political prisoners.

One released prisoner has a story that speaks volumes of the brutal regime built by deceased president Karimov. Critical journalist Muhammad Bekjanov fled the country in 1997, evading political persecution. Two years later, in an extra-territorial operation the Uzbek security services kidnapped him in Ukraine and forcibly returned him to Uzbekistan. Following extensive and hellish torture, Bekjanov confessed to false charges of attempting to assassinate the president. He was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment. As has happened so frequently in Uzbekistan, prison authorities arbitrarily prolonged his sentence citing alleged violations of prison rules. Until authorities finally released him on February 22, 2017 Muhammad Bekjanov was one of the world’s longest imprisoned journalists.

Another uplifting story to recently emerge out of Uzbekistan is that of human rights defender Azam Farmonov. Farmonov, being the head of a local chapter of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan, was arrested by police in 2006 on bogus extortion charges. His only crime had been defending the rights of farmers and disabled people in his region. Officials then tortured him until he confessed to the made up charges, and sentenced him to nine years imprisonment. He was released on October 3, 2017, on orders from president Mirziyoyev.

These two stories are part of larger picture in which Uzbek authorities recently have released dozens of well-known political prisoners – unthinkable only a few years ago. While the country remains authoritarian and human rights activism, political dissent and exercise of free speech are still dangerous activities, the developments prove that defending human rights is worth the effort – without the continuous attention brought to their cases by human rights activists, it is highly unlikely that any of these individuals would be free today.

Tajikistan in crisis: hundreds imprisoned on political grounds

While Uzbekistan has slowly made some progress on rights; Tajikistan has progressed rapidly into a rights crisis. Early manifestations of the crisis can be traced back to early 2013 when the country was preparing for presidential elections in November. In springtime businessman and former Industry Minister Zaid Saidov declared his intention to form a new opposition party – “New Tajikistan” – as well as his plans to run against the sitting president in the upcoming elections. When Saidov returned to Tajikistan from France, on May 19, 2013, police immediately arrested him. The same year he was sentenced to 26 years imprisonment on trumped-up charges of fraud, polygamy and statutory rape. Authorities later added another three years to his sentence.

The prosecution of Saidov was predictably marred by extensive flaws and violations of due process, one of the most striking being that the regime targeted his legal team. Shukhrat Kudratov, a celebrated Tajik human rights lawyer, was arrested in the summer of 2014 after drawing public attention to the case and filing complaints about irregularities in the legal proceedings. In return the regime sentenced him to nine years imprisonment on false charges of fraud and bribery. Other members of Saidov’s legal team have likewise found themselves in the government’s crosshairs and come to suffer similar fates.

While 2013 saw the presidential elections – which sitting president Rahmon expectedly won with a landslide following extensive election fraud – parliamentary elections took place in the spring of 2015. In the run up to the elections authorities launched a smearing campaign against the country’s main opposition party, the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), as well as a series of harassment and intimidation targeted at party members. The Norwegian Helsinki Committee was present in the country on election day and observed no signs of a free and fair election, which came as a surprise to no one, least of all to anyone in Tajikistan. What was a surprise on the other hand was that the Islamic Renaissance Party – at the time estimated to have approximately 40 000 members and vast scores of sympathizers and supporters – lost both seats in parliament, due to election fraud, rendering the parliament merely and thoroughly a rubber-stamp institution.

Following the fraudulent elections of February 2015, the regime intensified its crackdown on the opposition and in particularly the Islamic Renaissance Party. Numerous high-ranking party members were forced to flee the country during the spring and summer, feeling the heat of the government’s fury. After an alleged coup attempt in August, that the authorities pinned, without any semblance of credible evidence, on the IRPT, the Supreme Court banned the party in September and declared it a terrorist organization. Then the purges began. Police rounded up and arrested most of the party leadership still in the country, and has since arrested hundreds.

Most of the party leadership was then, on June 2, 2016, sentenced to lengthy prison terms on false charges of attempting to overthrow the government. Two party deputies, Mahmadali Hayit and Saidumar Husaini were sentenced to life in prison. Other high-ranking party members such as Rahmatullo Rajab, Sattor Karimov, Kiyomiddini Azov and Abdukakhori Davlat were handed down 28-year sentences. While others again were sentenced to terms ranging from 14 to 25 years. All of this in retaliation for their peaceful and legitimate work as politicians.

Having dismantled, outlawed and imprisoned the opposition, the Tajik government continues its crackdown unabatedly and enthusiastically, now and then shocking the international community by, among other abhorrent lows, kidnapping and forcibly returning critics from abroad before torturing and imprisoning them. In a recent case prominent journalist Khayrullo Mirsaidov was sentenced to eleven years imprisonment on June 2018. The authorities went after him with false charges after he spoke out about government corruption, adding yet another name of the ever-growing list of political prisoners in Tajikistan.

Turkmenistan – prison disappearances

While the situation is deteriorating by the day in Tajikistan and small steps of progress can be seen in Uzbekistan, the situation remains stably abysmal in Turkmenistan. Because of the very nature of the Turkmen regime – Turkmenistan is one of the world’s most repressive and closed countries – it remains impossible to pinpoint the number of political prisoners. What we do know with certainty however is that at least 111 political prisoners are forcibly disappeared in the Turkmen prison system. Neither their families nor anyone else in the outside world know where they are or even if they are still alive. Another thing we know for certain – from accounts from the lucky few having made it out of prison alive – is that prison conditions are hellish and torture and other ill treatment rampant. As is the case in Uzbekistan, Turkmen prison authorities are likewise fond of arbitrarily extending prison terms indefinitely.

As dispiriting and dreary as the current condition in the country is, this spring those of us that follow Turkmenistan enjoyed a rare occasion to rejoice. On May 19 authorities released journalist Saparmamed Nepeskuliev. Nepeskuliev was arrested in the summer of 2015 andframed with drug possession. A court sentenced him to three years imprisonment after which he disappeared into the Turkmen prison system. No one knew his whereabouts, and no one had heard from him until he was released having served out this three- year prison term.

Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan – relatively stable, relatively low number of political prisoners

Both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, neither by no stretch of the imagination beacons of human rights, are home to considerably fewer political prisoners than their neighbors. However, despite some prominent releases in recent years, Kazakhstan has recently seen a relative upswing in political imprisonment, where anyone with genuine or perceived links to exiled opposition figure Mukhtar Ablyazov will be targeted by the government.

In Kyrgyzstan the most striking case is that of Azimzhan Askarov. Askarov is an ethnic Uzbek human rights defender who had worked to uncover police violence in the south of Kyrgyzstan. When ethnic unrest between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz shook the south of Kyrgyzstan in 2010 he was documenting the violence. Authorities arrested him and charged him with trumped-up charges, including that of complicity in murder. He was then sentenced to life in prison. Despite protests from the United Nations, he remains imprisoned.

Why care?

Why should someone residing in a democratic country spend time worrying about political prisoners in Central Asia? And, even more so, why would anyone living in Central Asia risk persecution and prosecution by speaking out about the issue?

Those who advocate on behalf of political prisoners do so not only because it is impossible to remain indifferent to the extreme human suffering involved including brutal torture, unjust and lengthy sentences, hellish prison conditions etc. Those who fight for thefreedom of political prisoners do so also because the efforts bear fruits. After all, without the constant pressure and attention brought by human rights groups and others, authoritarian regimes have no incentive to release prisoners they would rather keep silenced and locked up in a cell. Untiring and unrelenting work towards Uzbekistan is now rewarded by releases by the dozen. Now more than ever before the same attention is needed towards the enormous problem of political imprisonment in Tajikistan. Then and only then, when the Tajik regime feels the heat of massive attention and international pressure, can one dare hope to see releases and a political thaw.