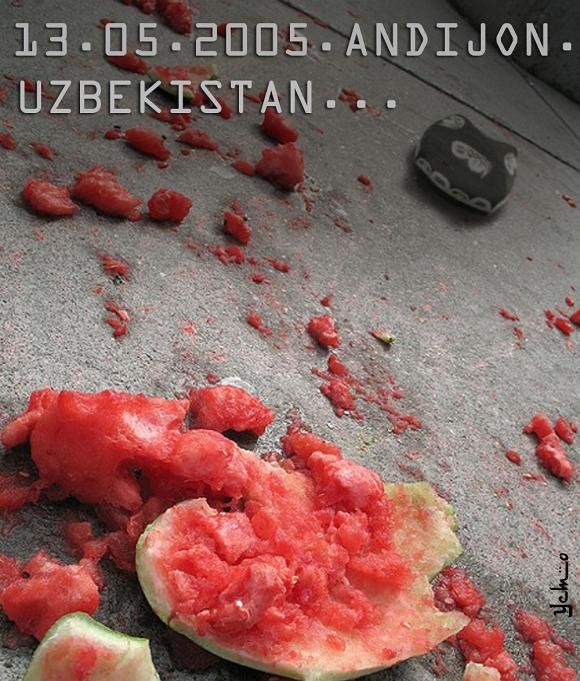

On 13 May 2005, government troops surrounded crowds of peaceful demonstrators in the town of Andijan in Central Asia’s Ferghana Valley. Unprovoked, they opened fire on men, women and children, killing hundreds. In the aftermath of the massacre, Uzbek authorities closed down international news agencies, initiated large-scale crackdowns on civil society, journalists and religious groups. Today, Uzbekistan is considered one of the most repressive states in the world.

No independent investigation of the tragic events of 13 May has been permitted, in spite of repeated calls by numerous states and non-governmental organizations.

Last month, on 24 April 2013, Uzbekistan underwent its Universal Periodic Review at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva. The Norwegian Helsinki Committee was among the organizations to have submitted alternative reports to the review, underlining current human rights concerns, contrasting the report submitted by the government of Uzbekistan itself and as presented by its delegation to Geneva.

Among the issues raised by the NHC was the Andijan massacre, as well as violations of a wide specter of key human rights in Uzbekistan. During the UPR, the Uzbek delegation had to answer to sharp criticism from numerous UN member states, including the lack of any real investigation of Andijan. Uzbekistan responded by saying that they consider the issue of Andijan “closed” and that they had said so repeatedly.

On the political level, Uzbekistan is controlled by President Islam Karimov and his circle, which also includes close family members. No election has ever been free or transparent in Uzbekistan, and engaging in politics on an independent platform is impossible in practice.

The use of torture in detention centers and prisons remains widespread, among the methods used during interrogations are beatings, electric shocks and simulated asphyxiation. While Uzbekistani journalists practice self-censorship for fear of retribution, restrictive laws and practice also means that anyone raising critical questions in the media risk persecution and imprisonment. The official media is completely state-controlled. Over the past four years, Uzbekistan has continued the practice of suppressing and persecuting members of religious communities considered to be “non-traditional”. Indeed, Uzbekistan has the worst record of violating the right to freedom of religion or belief among all former Soviet republics.

While remembering the victims of the Andijan massacre on 13 May 2013, the Norwegian Helsinki Committee encourages the international community, in particular the US and European NATO member states as the withdrawal from Afghanistan begins, to reiterate their demands for an independent investigation of what happened on this most tragic day in the history of modern Uzbekistan.

Photo: Association for Human Rights in Central Asia